Moving house

Well it turns out I’m not really angry enough, or stupid enough, to take on the whole of science. If you want to follow my somewhat mellower, more philosophical project, come on over to:

Stuck between two things

Philosophy is the battle against the bewitchment of our intelligence by means of our language. PI 109

Reading a lot of Wittgenstein at the moment. A moral from the Philosophical Investigations:

Many problems come from our wanting to treat something as something it is not. For Wittgenstein, this was treating the meaning of words as something in some special realm, or treating thoughts as mental objects to which only I have access.

Many problems come from our wanting to treat something as something it is not. For Wittgenstein, this was treating the meaning of words as something in some special realm, or treating thoughts as mental objects to which only I have access.

The solution is to look at how we use words and what actually goes on and figure out from that how to treat things. Starting with an idea of what something is and then forcing the thing into that idea only leads to problems.

The same basic problem is faced with the incursion of the scientific attitude into non-scientific areas of language.

We want to treat depression as a medical problem, with an entirely biological explanation, but this makes the fact that we often “catch” depression from events in our life seem quite odd – (“queer” in Wittgenstein’s terms).

We want to treat religion as making factual claims about the universe, but this makes the fact that people are converted to a religion and not just educated about it seem odd.

We want to believe that our experience takes place in the brain, but that makes the shared world we live in an odd place.

We want there to be a firm separation between subjective and objective so that we can put everything on the objective side in a bag marked truth and discard everything else as lightweight. But when we look at the world we find it much harder to fit things into the bag. What, for example, is money? Without our “subjective” acceptance of its value, the objective marks on paper or gold atoms are literally worthless.

I haven’t really understood it yet, but I think I’m on the right track.

The heap

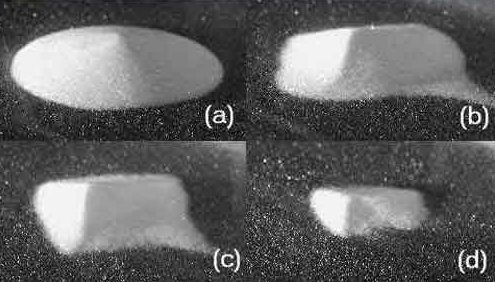

An ancient philosophical dilemma. How many grains of sand are there in a heap?

From wikipedia: The paradox of the heap (Sorites paradox) is an example of the paradox which arises when one considers a heap of sand, from which grains are individually removed. Is it still a heap when only one grain remains?

My solution is this. A heap of sand is a thing. A heap of sand is a concept. We are able to use the word to describe it, are able to use arguments and justifications in borderline cases. Each heap of sand is also a number of sand particles. The number of sand particles in heaps as opposed to piles or mounds is based on counting the sand in piles we decide are heaps. The edges of the definition are ambiguous, the existence of heaps of sand is not. Under certain conditions we might be happy to set a number, in others to take survey results, in another become totally confused and be unable to decide.

The argument is that we live our lives in a world both material and conceptual. This duality means facts about the world are fundamentally ambiguous. The material facts about sand can’t tell you how many grains are in a heap. The grammar of the word heap cannot tell you the chemistry of sand.

But the concept does not exist in the material world – we stand towards the world as if it is conceptually organized, there is no space for thought, for conscious interpretation. Any yet we share the concepts. They are communal. They are not my creation, but ours.

There are two basic epistemologies – the foundational of reductive science, and the contextual, of expansive conceptual life.

Scientific truth is ambiguous. The thing is matter organised conceptually, not either just matter or just concept. The boundaries of the heap are not consciously decided by us, the decision is made in the way we use the concept – the way we talk about heaps in different contexts. But it is still the thing there, the grains piled up. With both physics and gramatical certainty as its basis.

In the world there is such overlap between matter and concept that we become confused about how we are able to talk. We fear ambiguity lets in mystery, that it throws things somehow up in the air, but in reality an enmeshed and interweaved ambiguity is everywhere in our lives. That something is ambiguous does not mean that it is nothing (although it is nothing useful for science).

With the certainty of science glaring down at us, we are tempted to say there is no heap, the heap is just in our minds. That is the start of all this bother.

The philosopher

Philosophy is more rubbish than science by a mile.

Philosophy is more rubbish than science by a mile.

The first problem is how they fill their time – writing peer-reviewed papers, spending time researching and going to conferences, teaching undergraduates. What use is it for most people? Greatest philosophical breakthrough of the last 20 years anyone?

The extreme positions have already been plotted. There are no discoveries in philosophy.

While their modus operandi mimics science, they are so scared of the rigor, certainty and force of scientific argument, that they keep themselves hidden, quiet little mice of academia, making sure not to rock the boat and draw attention. Tending to a career.

Worst of all, they come up with words like ontology and epistemology (will write next), they debate the hard problem of something everyone does all the time. They use words which ring-fences unfathomable complexity; minute detail. (Such that surely only a professional philosopher could comprehend, of course.)

Well guess what? Philosophy is a science as much as documentary making or being a novelist.

There is the same difference between academic philosophers and philosophers as between english literature professors and novelists (of course they do sometimes overlap).

The subject matter is philosophy. Books and essays and arguments about abstract, conceptual matters.

Except there are no bastard philosophers to be seen. Plenty of novelists, but no philosophers. They used to exist. But now they don’t. They got swallowed up by the scientific attitude (and the old philosophers didn’t help by being utterly impenetrable).

Here is the definition. Philosophy is creative abstract thought. It is that easy.

Is there a need for philosophy? Doesn’t academic theory of philosophy that university professors do look pretty similar?

The old philosophers failed not in intent or genius but in accessibility. The biggest criticism of the best of them was arrogance and elitism. They created no vehicle for their ideas to get outside of a select few (perhaps they were squashed by religion).

My idea of philosophy is obviously a romantic ideal. Don’t you think its worth aiming for?

Faith, religious and non-religious, cannot defend itself from science (or rather in more confusing and accurate terms, all of a certainty’s defences against science are founded on connected certainties). Philosophy should be the buffer between science and life. Philosophy should be telling science to back off.

How do you interest a scientist in ontology?

Ok. It’s a bad word. Please keep reading. Ontology is a terrible word. Rings of something incredibly complicated. (see comments on philosophers, edited out of previous version).

If you feel like writing. Here’s a question. If not, read on…

The question

The question you need to ask yourself is simply this. What is real? What is reality like? If you had to describe it objectively, capturing everything, what would you say?

Scientists are a clever bunch. All my criticism is of science applied to the wrong things, not science as used in the right way.

The problem, in an impossibly abstract sense, is that scientists work on an incoherent ontology. It is not scientists fault in a way. They are by definition not interested in a conceptual argument.

The problem, in an impossibly abstract sense, is that scientists work on an incoherent ontology. It is not scientists fault in a way. They are by definition not interested in a conceptual argument.

In the most basic sense an ontology is just an abstract conceptual description of what is real. Science does deal with defining what is real, but only after you have decided what kind of questions you need answering, and what importance the answers have.

It is not in the interest of science to question the conceptual system in which their investigation takes place. The inevitable answer is that science does not provide the whole answer.

Scientists themselves don’t seem to believe that they have all the answers. They happily use concepts that lie outside of scientific investigation – the purpose of the investigation, for example. Because the ontology is everything it obviously decides the importance of everything, thats all.

Language does not comply to the laws of physics

Ontologies can be really easy.

I’ll try an ontology from the most coherent materialist angle possible:

I’ll try an ontology from the most coherent materialist angle possible:

Everything that happens is made of matter. Matter can be explained by the rules of physics, chemistry, biology and cosmology.

One part of the material world is brains and nervous systems in humans.

Living brains and nervous systems in humans generate a complex, communal form of life, experienced by each living and awake human.

Every fact about the world only matters to us insomuch as it is part of the brain-created, conscious, conceptually organized life we live. This life takes place in the material world, but a material world overlayed with a complex network of interconnected concepts which are shared by massive groups, cultures, societies and populations of humans. You obviously cannot see these in the normal sense.

Of course everything real is a concept that is made of something. But tell me how where a concept is, is the most useful part of the explanation?

Lets try one. The concept of the novel. All the paper and ink in books and led and computer chip as well, on which they are being written. And add the interconnected neurons of novelists – the ones that do the thinking, and the writing, and the history and criticism of novels and the great novelists, and all the reading.

The question is, so what? I know what a novel is. There is no scientific discovery about paper or LEDs that will help me explain what a novel is.

And here we hit the sticky point. We get confused talking about our own brains. There are discoveries about the brain that are obviously yet to be made. The question is the most useful explanation of how the neurons are connected.

I would argue that the scientific explanation is not very useful in conceptual matters. The best, and most comprehensive possible answer of what the neurons are doing, the organisation of the atoms, is the description of the practice of reading and writing novels. This is inevitably an expansive inquiry based on finding out about the connected concepts, practices and ideas – the grammar of our form of life, to put it in Wittgenstein’s terms.

You explain what a novel is by explaining what reading and writing are, you explain narrative and characterization, the history of novelists, the science of printing and of neurobiology, the anthropology of storytelling. All these things and more give the best, most complete explanation of the novel. (the words explanation and description here mean the same thing).

How can you say that life is not real?

It makes no sense to say that life is not real, but that is exactly what many people seem to believe.

It makes no sense to say that life is not real, but that is exactly what many people seem to believe.

Basically, we all bloody well know that we are conscious. That we are all living lives.

There is all this debate about the science of consciousness. We discovered consciousness long ago, but have yet failed to comprehend the implications of the discovery.

We know that our brains do subjectivity, that this is “what it is like to be your brain and nervous system”. We have known the ontology for a long time. But who would herald the discovery of something they were already plainly aware of.

No. We found out that conscious life took place in the brain, and not for example, the lungs. But we were not particularly interested. The logical conclusions are still sinking in.

These thoughts are so far from the scientist’s interests that it is clearly possible to discount them entirely.

The scientist’s question – “how do I find out what is real?”

The scientist’s answer – “it’s what I do”.

1.What is real? Come on you scientists and atheists and rationalists of all shapes and sizes. For the sake of nothing but inquiry and curiosity, indulge me in this trivial matter. What do you think, in the most abstract terms you can face using, is real? What ontology are you working from? Do it in 140 if you like.

The conceptual pop

We are so close. We have an almost complete picture of reality. There is just one more step to go.

We know that the world we experience, that we share with everyone else, is a world made inside our head. We know that the world exists, we know that our senses perceive it, and we know our brain’s recreate that same world – adding in loads of really complicated stuff as it goes.

Our problem is that this argument still looks like one for some form of solipsism. Our entire argument is deformed by the fact that we do not have the values right in the picture.

For our enquiry started out trying to explain this world in which we all live. It ended up saying this world was not the real one.

The discovery that consciousness took place in the brain and the subsequent feeling that this changed the inquiry, is not the same as doing an operation for a broken bone and finding cancer. It is like the doctor becoming disinterested in surgery because of something he found while operating and turning his hand to carpentry.

The leap we must make is to flip our value system, our judgement system, our entire conceptual structure, to reflect the fact that the stuff that happens in all of our heads is the only thing of value to us, and that it is also a shared phenomena.

The conceptual pop happens when you see that consciousness might be a sometimes inaccurate virtual reality of our shared world. But it is all we have. We have to call it reality, we just have to, its all we’ve got. But it helps to think of it like virtual reality, so I’ll call it (v)R.

The difficulty is that the rules of the investigation change massively when you pop. No longer is it a clear-cut matter as to what is real. Ambiguity and shifting cultural sands lie all around. No longer is there a reductive system of investigation by which reality is pinned down. The conceptual system that explains our (in brain) reality is utterly expansive and interconnected.

Reality now conforms, not to the rules of causation, but to the rules of narrative, the rules of grammar.

The fall out from the pop is to accept that the human sciences – human evolution, psychology and sociology, are in a different bracket of investigations to those whose subject matter is outside the reality. Of course they do talk about material facts – the glands of emotion, the genes of gangs.

The fall out from the pop is to accept that the human sciences – human evolution, psychology and sociology, are in a different bracket of investigations to those whose subject matter is outside the reality. Of course they do talk about material facts – the glands of emotion, the genes of gangs.

But they also have to try and generalize the narratives of living humans. How to you generalize stories? Clearly in a different way to averaging data.

I find it hard not to get waylaid in these thoughts. So many confusions come from our inability to clear our ears at this altitude. If you make the pop and start calling THIS reality, you’ll start to see the oddness of putting all the truth into natural science.

When you pop out into the organized, conceptual, interconnected and narrative brain-created human-reality that we all call home, you’ll see that everything that has meaning and value is completely different in kind to the facts of matter. The truths are based on certainty and action, the concepts are based on stories, and everywhere we tread disconnects and reconnects the connections in new and different ways.

We must stop wishing that science could understand this massively complex shared (v)R world from the outside, and get on with figuring it out from where we are.

It is such a simple picture. The world – my head – our world. Such a simple picture – shared virtual reality. Why isn’t it obvious?

Hemispheres

Psychiatrist Dr Iain McGilchrist speaking here about the two halves of the brian:![]()

“The difference is essentially one of attention. It might not sound important, but it is.

“If you look at birds, we know that chicks use the eye that is connected to their left hemisphere to get seed, to be able to pick out that detail against the grit. The other one is watching out for predators. Taking the wider view.

“The left hemisphere has its own agenda, which is to help manipulate and control the world (hence it controls the right hand for grasping). The other hemisphere has no preconceptions, and simply looks out to the world for whatever there might be. In other words it has no allegiance to any particular set of values.

“It matters because, over the course of time, there has been a shift towards the view of the left hemisphere. There has been a series of shifts backwards and forwards, but with each shift there has been a gain of ground by the left hemispheres view of the world – the view, essentially, of the world as a mechanism.

“That is because it is a very coherent, self-refering system. It is a beautiful model which allows things to be simple, graspable and usable. It is a bit like the difference between a map, and the land the map represents.

“It results in a visualizing and self-refering world, in which doctors, teachers and policemen find, they spend an awful lot of time planning, reporting and analysing what they are doing, and not doing it.

“We have substituted a rather lifeless, mechanical, fragmented picture of the world. Which has robbed it of its complex, changing, interconnected quality. That actually has a huge impact on our view of ourselves as human beings and what we are doing on the planet.

“We are in the process of destroying the planet through a need to be constantly grasping and using. We miss out on the non-mechanical aspects of our existence, and see ourselves as simply rather clever machines and a lot of other things get neglected.

Articles of faith

The New Atheists or scientists, as I like to call them, don’t just have a problem with organised religion. They have a problem with the very concept of faith.

The New Atheists or scientists, as I like to call them, don’t just have a problem with organised religion. They have a problem with the very concept of faith.

In science’s language, the definition of faith is this – living your life as though human-created stories are real things in the world.

Making concepts real is what faith does, and all concepts, by definition, are human-created. Faith is simply a belief that a belief is real.

I, for example, have faith in the existence of love. I know it cannot be explained as the causal link between two brains or organisms. I know love only exists because I believe it’s existence is real. But I also know that my faith in love, along with everyone elses, is all that keeps love in existence. I could inspect as many brains as I like, and I will not find love, only the brain parts which make the concept possible.

So how can I have faith in something’s being real, at the same time as knowing that it only exists as a concept? Doesn’t this make it an illusion?

This all depends how you want to define reality. There is no absolute rule stating that you have to restrict the concept of reality to exclude concepts. You may choose to believe that there is such a rule, and you can make your arguments around assuming that rule is true, just as many atheists do. That just isn’t a good way to argue (to assume your answer).

This all depends how you want to define reality. There is no absolute rule stating that you have to restrict the concept of reality to exclude concepts. You may choose to believe that there is such a rule, and you can make your arguments around assuming that rule is true, just as many atheists do. That just isn’t a good way to argue (to assume your answer).

Personally, I wouldn’t want my concept of reality itself not be real – for me that would be confusing. If you think it works, let me know how.

So if you allow conceptual as well as material reality in, what then?

Well you have to accept that things like love, happiness, joy, freedom, responsibility and community are real, but only in so much as we believe in them.

Actually, the relationship is much more complex than that, we’re not talking about twinkerbell here. Faith, defined as a belief that a belief is real, is a necessary condition for the existence of our conceptual reality. But the articles of faith still have to acted upon to make them real. It’s no good believing love is real when no-one is actually in love.

Now here’s the crunch. Communal conceptual realities (or you could call them faith communities I guess, or folks that share the same story) that do not include the discoveries of science don’t personally suit me. I’m an atheist, and always have been.

And there is no doubt that literalist religious conceptual systems can cause harm in some cases – the intelligent design lab biologist for example, or the Al Qu’aida bomber. However, most people who believe in concepts that massively contradict material reality – that the world is young, the people go to a special place after death and so on – lead pretty normal lives, considering.

The point is that there is so much more besides, which fits in just perfectly with the material reality, but which still make use of our ability to live our lives within complex and beautiful narratives. Here are just a few examples:

Awe and wonder. Richard Dawkins prefered conceptual reality, built on our emotional (concept) reaction to beautiful(concept) natural (concept) scenes.

Golden Rule. Love thy neighbour. Perfect consequentialist rule of thumb.

Humanism. Ain’t life great. Couldn’t it be great for everyone.

Humanitarianism. Ain’t life shit. Couldn’t it be great for everyone?

Progress. I believe there will be a situation in the future, which could be better or worse depending what I do now.

History. What I am now is because of great-great-great-great-great grandpa’s awesomeness.

Evolution. How brilliant is it that complex life, or life itself, even exists. How great that the ancestors survived and changed.

Freedom. I can do anything.

Community. We can do anything.

Creativity. I can improve the world by making interesting and beautiful things.

and last of all Depth. There are such things as shallow and deep experiences, and the deeper ones are often better.

There are tons more, let me know your favourite.

Rationalist judo

There are some things people cannot say. It’s not that they’re stupid, or that they’re particularly closed-minded, it’s just that saying certain things makes their world fall apart.[1]

There are some things people cannot say. It’s not that they’re stupid, or that they’re particularly closed-minded, it’s just that saying certain things makes their world fall apart.[1]

“Myth” isn’t a word that can be used by the person who believes in the myth. There are enough magazine articles about the myth of sexuality or love or democracy or progress, to see it is a word that is used to undermine. You can’t have a debate about a myth without first accepting that someone accepted it as true – but always in the past tense. It is impossible to have a discussion about your own myths.

What is more, these stories-taken-as-real aren’t limited to Zeus turning into a bull or Jesus coming back from the dead. Think of the myths of genius or heroism. In the scientific sense there are no geniuses or heroes, but even the hardened rationalist might see the utility in keeping the stories.

The problem is that for these stories to find a place in the world, they have to sit in the place of scientific facts. Myths aren’t just stories, like films and novels, they are stories that people believe are true and which serve a purpose in people’s lives. They are stories that are lived by, are lived into existence, are accepted as (by necessity unseen) parts of the world.

The problem is that for these stories to find a place in the world, they have to sit in the place of scientific facts. Myths aren’t just stories, like films and novels, they are stories that people believe are true and which serve a purpose in people’s lives. They are stories that are lived by, are lived into existence, are accepted as (by necessity unseen) parts of the world.

So people who believe human-created stories are real and want to keep them – and lets face it, in some form that includes all of us – are faced with a dilemma when asked to defend their beliefs.

They can’t, after all, discuss them as myths. That punctures the balloon which gives their life its certain kind of meaning.

And they can’t say they’re not factual claims, because that would mean they should treat them as stories, which they don’t.

So their only options are to defend them as factual claims, set up defences so as to persuade themselves that the facts are not where the scientist says they are, and pay as little attention as possible to the whole debate.

Which is where the modern kind of atheist comes in, constantly asking them to defend their myths as facts.

Which is where the modern kind of atheist comes in, constantly asking them to defend their myths as facts.

But, as we know, the statements of religion are not factual statements, except obviously the myth believer has to say they are in order to keep the myth alive.

And the atheists know they are not facts, and they also know that the upholder of the myth cannot say that. They know the myth believer can’t even entertain the thought that they are myths, because that kills them as myths and makes them into stories.

The new atheist strategy seems to be to try and bully the myth believer into facing the scientific reality of the thing the scientific reality destroys. This is by no means an obviously good thing. It is rather an act with moral consequences, the justification for which has to come down to an argument about the worth of the myths in people’s lives. This is an argument that in some cases is obviously well made, in others clearly not, and in most utterly ambiguous. Even where the moral case is made, the fact that the myth only exists because it is somehow insulated from science means telling someone their belief is a myth is a very stupid way of trying to get them to change their mind.

There is a bludgeoning unsubtelty about some atheists’ approaches to religion.[2] Myths have to be approached crabwise, from the side – from the facts about their effect, their impact on people’s lives and their value. Straight on, all you end up doing is making enemies and forcing the mythics in more and more defensive directions. Science either needs to make its own myths, or just back off.

_______________________________________________________________________________________

1. This post is in some ways a reaction to Lisa Miller’s editorial in Newsweek, much criticised by Bloc Raisonneur, Why Evolution is True, Mind Droppings, Reason.Science.Metal , Think Atheist and Poohsthink – although it gets a friendlier and altogether more subtle reading from In Living Colour.

2. I mainly mean sciencey atheists like Richard Dawkins, the Reason Project and Pharyngula, who I’m sure are quaking in their boots.

Once upon a time…

This talk from physicist Lawrence Krauss is fascinating. It’s a masterclass in how scientists and narrative are bound together – it tells stories about the universe, as science believes at the moment it really is – 13.72 billion years old, flat in a 3D sense and expanding at an accelerating rate. Scientists and atheists like Depth Deception, Brother Richard, Prometheus Unbound and The Good Atheist love it, although all for different reasons.

The problem is that the questions of interest to science drive the narrative, in a way that is far from scientific or rational. For example, he argues that less than 1% of the universe is planets and stars and all that we see and are. The rest is dark matter (30%) and dark energy (70%). So on the scale of the universe, we’re completely insignificant.

Now this whole set of facts is clearly generated by the scientific interest in solving the conundrum of dark matter. What on earth do the facts thus gained have to do with the significance of our life, planet or solar system? In what respect is living matter equal in value to dark matter? In equations about the universe it is equal, for sure, but not in our actual lives. There’s a mother and baby on one railroad track, a pile of dark matter on the other…

Now this whole set of facts is clearly generated by the scientific interest in solving the conundrum of dark matter. What on earth do the facts thus gained have to do with the significance of our life, planet or solar system? In what respect is living matter equal in value to dark matter? In equations about the universe it is equal, for sure, but not in our actual lives. There’s a mother and baby on one railroad track, a pile of dark matter on the other…

As tongue in cheek as this talk is, there is something serious going on. Atheists, like everyone else that ever lived, need their stories. The success of this talk clearly derives from this need. What is more there’s clearly a quasi-theological argument going on. The fact the universe is “flat”, for example, means the total energy is zero so you don’t need to posit the existence of a deity to have kicked it off (as if that is what physicists would posit if the universe were not “flat”).

One of the reasons the talk is so engaging is that Krauss’s universe seems to have a character, but that character is of a massive, cold and uncaring thing – like a god who doesn’t care. But the universe has no character whatsoever. It’s size is not, for instance, large – there’s no comparison for that word to make any sense.

In one way, I’m being pointlessly sour. This is just funny stuff about the universe, meant to make you think, to communicate the facts in a fun way. But sadly, this stuff is the closest atheists come to having something to believe in. And in this talk, the overriding narrative is fundamentally confused.

At one point, Krauss says cosmology has uncovered the most poetic fact about the universe – that the explosion of stars generates the atoms that end up in our body:

“Forget Jesus,” he says. “The stars died so you could be here today.”

But the talk ends on a total downer on the big picture of the universe:

“It’s big, rare events happen all the time, including life, and that doesn’t mean its special.”

The trouble is, Krauss’s cosmic narrative is generated as a way of interesting us in the facts and does not seem thought through as a narrative. There is a feeling that the narrative naturally follows when you know the facts. It is obvious that our lives are insignificant when you know the scale of the universe. It is obvious that our lifespans mean nothing when you know the timescale of the universe.

But these things simply are not true. The cosmological calculus has no necessary bearing whatsoever on whether or not we think life is special, purposeful or good. The value of life is not found naturally occurring in the universe – thats a religious thought. We make up the values, not the stars.

If we want to think life is special we can construct a narrative to do that – using whatever tools we chose. The facts by themselves are only physically or causally connected. The conceptual connection is made up by us and simply does not exist in the universe before we find it there.

If we want to think life is special we can construct a narrative to do that – using whatever tools we chose. The facts by themselves are only physically or causally connected. The conceptual connection is made up by us and simply does not exist in the universe before we find it there.

So whether we chose to fit a story about the universe and the people curious enough to find out about it into a good story or bad is up to us. We decide.

Humans have to believe in something and it is irrational not to make the most of this ability. It is a cowardly lie to pretend the narrative forces itself upon us. (Although I don’t think Makouli will agree).

Why not believe in something good, that our lives are meaningful, that there is a point to existence? This talk gives much to inspire, but does much to purposfully destroy all faith in life at the same time.

leave a comment